Long-term graft protection requires careful monitoring

The first few days after transplant are critical; tacrolimus levels on day 2 and day 5 have been shown to be early predictors of rejection.1,2 Even after that initial hurdle, the risk of inadequate immunosuppression continues to loom and threatens positive outcomes.3,4

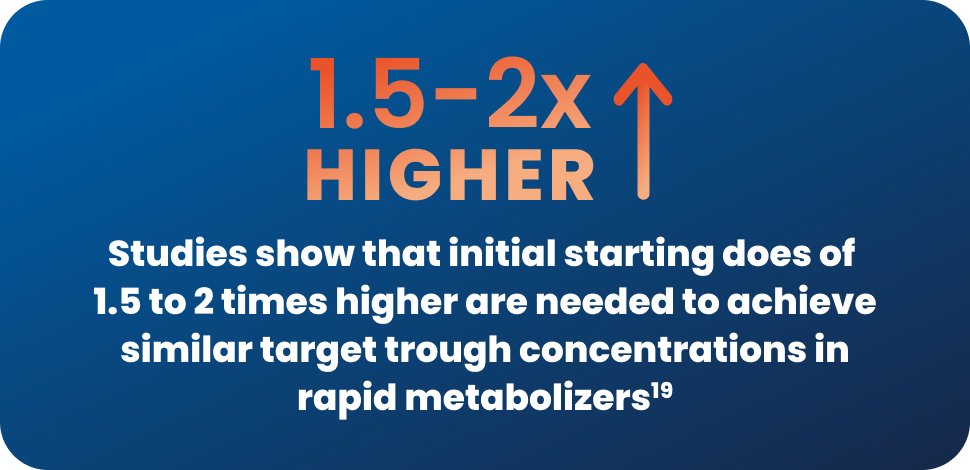

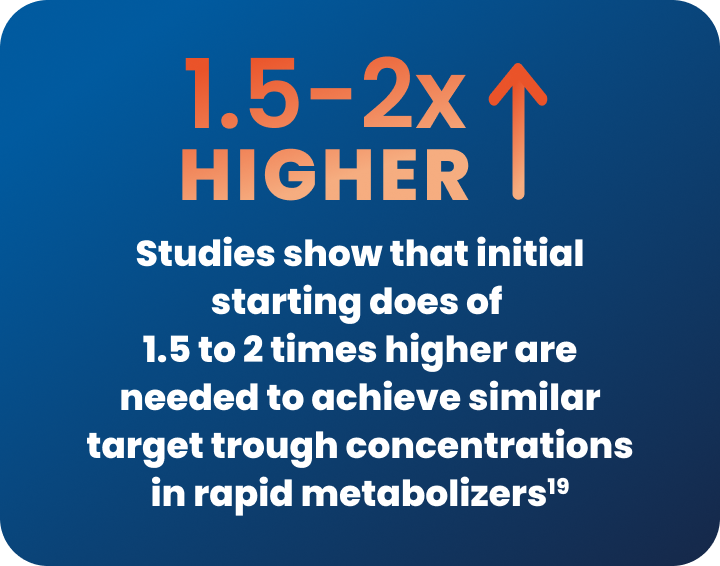

Despite advancements in kidney transplantation, significant disparities persist in clinical outcomes across different patient populations. African American and older kidney transplant recipients present unique challenges in immunosuppression management, driven by differences in immune responsiveness, drug metabolism, and competing risks such as infection, toxicity, and comorbidity burden.5-8

Patients face numerous challenges during the post-transplant journey

Protecting the patient’s graft from rejection is just 1 aspect of post-transplant care to consider. Numerous other challenges remain, including:

- Tacrolimus is characterized by a narrow therapeutic range—and numerous adverse outcomes are associated with levels outside of that target range3,4,9

- Side effects and complex dosing regimens can contribute to declining adherence10-12

- Nephrotoxicity impacts graft survival13

- Infections are a common cause of morbidity and mortality14

hidden text

With so much complexity, post-transplant care requires more than just preventing rejection.

It demands a thoughtful, patient-tailored approach to immunosuppression.

References: 1. Undre NA, van Hooff J, Christiaans M, et al. Low systemic exposure to tacrolimus correlates with acute rejection. Transplant Proc. 1999;31(1-2):296-298. 2. Borobia AM, Romero I, Jimenez C, et al. Trough tacrolimus concentrations in the first week after kidney transplantation are related to acute rejection. Ther Drug Monit. 2009;31(4):436-442. 3. Hesselink DA, Bouamar R, Elens L, van Schaik RH, van Gelder T. The role of pharmacogenetics in the disposition of and response to tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(2):123-139. 4. Kershner RP, Fitzsimmons WE. Relationship of FK506 whole blood concentrations and efficacy and toxicity after liver and kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;62(7):920-926. 5. Oetting WS, Schladt DP, Guan W, et al; DeKAF Investigators. Genomewide association study of tacrolimus concentrations in African American kidney transplant recipients identifies multiple CYP3A5 alleles. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(2):574-582. 6. Taber DJ, Gebregziabher M, Hunt KJ, et al. Twenty years of evolving trends in racial disparities for adult kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2016;90(4):878-887. 7. Purnell TS, Luo X, Kucirka LM, et al. Reduced racial disparity in kidney transplant outcomes in the United States from 1990 to 2012. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(8):2511-2518. 8. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). OPTN/SRTR 2023 Annual Data Report. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annualdatareports 9. Staatz CE, Tett SE. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(10):623-653. 10. Taber DJ, Gordon EJ, Myaskovsky L, et al. Therapeutic needs in solid organ transplant recipients: The American Society of Transplantation patient survey. Am J Transplant. 2025;25(12):2565-2577. 11. De Barros CT, Cabrita J. Self-report of symptom frequency and symptom distress in kidney transplant recipients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1999;8(6):395-403. 12. Nevins TE, Robiner WN, Thomas W. Predictive patterns of early medication adherence in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;98(8):878-884. 13. Xia T, Zhu S, Wen Y, et al. Risk factors for calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity after renal transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:417-428. 14. Karuthu S, Blumberg EA. Common infections in kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):2058-2070. 15. Thölking G, Fortmann C, Koch R, et al. The tacrolimus metabolism rate influences renal function after kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111128. 16. Trofe-Clark J, Brennan DC, West-Thielke P, et al. Results of ASERTAA, a randomized prospective crossover pharmacogenetic study of immediate-release versus extended-release tacrolimus in African American kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(3):315-326. 17. Staatz C, Goodman LK, Tett SE. Effect of CYP3A and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of calcineurin Inhibitors: part I. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(3):141-175. 18. Kuehl P, Zhang J, Lin Y, et al. Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat Genet. 2001;27(4):383-391. 19. Birdwell KA, Decker B, Barbarino JM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for CYP3A5 genotype and tacrolimus dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;98(1):19-24. 20. Egeland EJ, Robertsen I, Hermann M, et al. High tacrolimus clearance is a risk factor for acute rejection in the early phase after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2017;101(8):e273-e279. 21. Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M, et al. Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: the dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):388-399. 22. Massey EK, Tielen M, Laging M, et al. Discrepancies between beliefs and behavior: a prospective study into immunosuppressive medication adherence after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99(2):375-380. 23. Massey EK, Meys K, Kerner R, Weimar W, Roodnat J, Cransberg K. Young adult kidney transplant recipients: nonadherent and happy. Transplantation. 2015;99(8):e89-e96.